If you don't know, I also edit a poetry review journal, Galatea Resurrects. So since I wanted to write on Tim Armentrout's wonderful poetry chap, All This Falling Away, for SitWithMoi, I decided to just review it for the current Issue #20 and smooch two birds with one marshmallow (so to speak). You could go to the link to read the review (and many other reviews of wonderful contemporary poetry books!). But you can also see its illustrated version below, to wit:

All This Falling Away by Tim Armentrout

(Dusi/e, Switzerland, 2007)

Tim Armentrout’s 2007 Dusi/e chap, All This Falling Away, presents what looks to be a single poem on 47 pages. It’s a fascinating project for several reasons.

First, there’s 14 lines on each page—let’s assume my random check of five pages makes it so—and so one wonders if this is also a single stanza long poem. I could believe this to be the case, and that the page-breaks are done simply because 14 lines is a good fit on the chap’s 4.5” x 4” page. I want to believe this to be the case because, for my first read, I read it all in one sitting and there was a seamlessness to my read, unbroken by the page-break.

What is marvelous about reading this poem is the sense of hushed-ness that surfaces. All these words! And yet. These have got to be among the quietest words I’ve ever read. You read the poem and you’re drawn into its world and continue reading and turning the page and reading and turning the page…and the experience befits its underlying concept, as captured by its title, of “All This Falling Away.” That is, the “All” that falls away could be the rest of the world until you are residing solely within the world/words of this poem. It quiets down the rest of the world, making you (or me) calm down to rest within the poem. That’s quite a feat! Sorta reminds me of that Greek Temple—at Delphi?—whose path from bottom of mountain was designed to meander rather than shoot straight up, so that the pilgrim, as s/he approaches the Temple, is encouraged to leave the rest of the world behind whilst meandering so that when the pilgrim finally arrives s/he is solely focused on the Temple and its oracle…

I’m struggling to articulate this poem’s effect. Maybe because its words are meditative? I’m not sure if reading an excerpt would generate this same effect—but I’ll randomly pick three pages worth of text and see if you, Dear Reader, can sense what I’m talking about:

Cautious steps

Through snow dust

Early Monday

Dark fades from mountaintops

New day’s nausea

Disorienting sleep

Walk slowly into graves

Convinced of morning’s

Cruel signature

Sunburst pain

Explosion above the hips

Dawn abandoned hope

Gray

Like milked excuses

A desire for stomachs

Calm as Tuesday

Cold breakfast in the snow

Reinventing ritual

With a hand shovel

Sage and crystals

Burial before earth freezes

The preservation of life

Does not guarantee its quality

Laboratory rejection

Is still a death sentence

Fragmented

By glory and illusion

Rising with winter sun

Disastrous leadership

Scanned crowds down lines

Of pointed fingers

The search for home

Where blame can rest

On thieves of Wednesday’s innocence

Responsibility minimized

Sliding in and out of back doors

Shadowed compassion

History has been shaved

Sounds of bone echo

Memories of meat

Refusal to admit

Flesh is an opaque evil

Well, I don’t know about you but this excerpt, for me, does generate (though not as strongly of course as the entire poem can) the effect of stillness I described above. And in reading over this excerpt, I also realize that the poem’s line-breaks are well-chosen to facilitate a rhythm in which one can get lost (in most cases, the line-break does facilitate a pause, at least in my read).

So if you think about it, it’s quite impressive for the poet Tim Armentrout to have maintained the same emotional plane (understated resonance?) for 658 lines.

This poem also made me think of my single experience of scuba diving. Just one time since I can’t swim, preventing me from participating in much water sports. But, once, I did dive and for that experience learned a bit about the importance of not rising too quickly back to the top after you’ve descended. In consciously controlling my ascent back up to the water surface, I recall thinking that the water was sliding slowly off of my body—which is interesting for feeling so real despite its falsity in that I was immersed the whole time. That slow ascent, with matter falling away from my body, is a bit like the experience of reading All This Falling Away. During my ascent, there, too, was a hushed-ness to the experience (no doubt because I was totally immersed and so (almost) couldn’t hear my companions, birds, wind, etc.).

And as I consider the comparison of my reading experience to rising upwards from the depths of a sea, I realize that the body—the narrator—is not the one falling. It’s external stuff (e.g. water) that’s falling away from the body. To reveal the true body. What synchronicity! Because the epigraph to Armentrout’s poem—perhaps the conceptual underpinning to the poem—is the following:

as the

spirit

wanes

the

form

appears

-Charles Bukowski, “art”

Is Bukowski or Armentrout talking about the dispelling of the ego to facilitate art’s appearance? Much in the same way that I’ve thought of my job as a poet as partly one of getting out of the way of the poem? I’ll just leave the questions there…

…but will note further that for this poem, it didn’t seem to matter much what the words were saying (though their sounds did matter for facilitating rhythm). What mattered most was the sensory experience engendered—in this case a calmness calming, a meditation, whatever one calls it. But there’s something “pure” about the experience as it wasn’t tainted by the words’ definitions even as the words exist. Perhaps that purity is … the form.

If Armentrout wrote a poem manifesting pure form, then he accomplished something difficult to achieve. I believe he did—I bow to him for this poem.

+++++++++++++++++++++

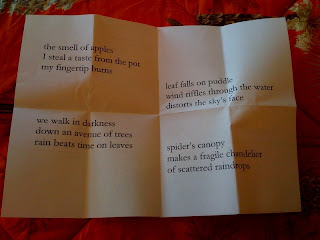

So that was my review -- but here's a bonus for SitWithMoi readers. I talk in the review about the "dispelling of the ego to facilitate art's appearance" and the notion of the poet "getting out of the way of the poem." Note here the design of the chap, specifically the verso (inside) of the front and back covers, like so:

It's a "Twin Pack" and the text says "Open one now! Second one stays fresh!" Could this not be a poetics metaphor? Deplete the first container (the poet eliminating his ego) and you're left with a twin who "stays fresh" (the poem which retains the author's "I" but is more than the author's self). Poets don't last but poems can last if they become beloved by generations of readers, if those poems "stay fresh." Well, that's my read/view anyway, she adds cheerfully...

And now, where shall we "shelve" Tim Armentrout's lovely chap? Well, I think it looks lovely on a big-hearted twig chair!